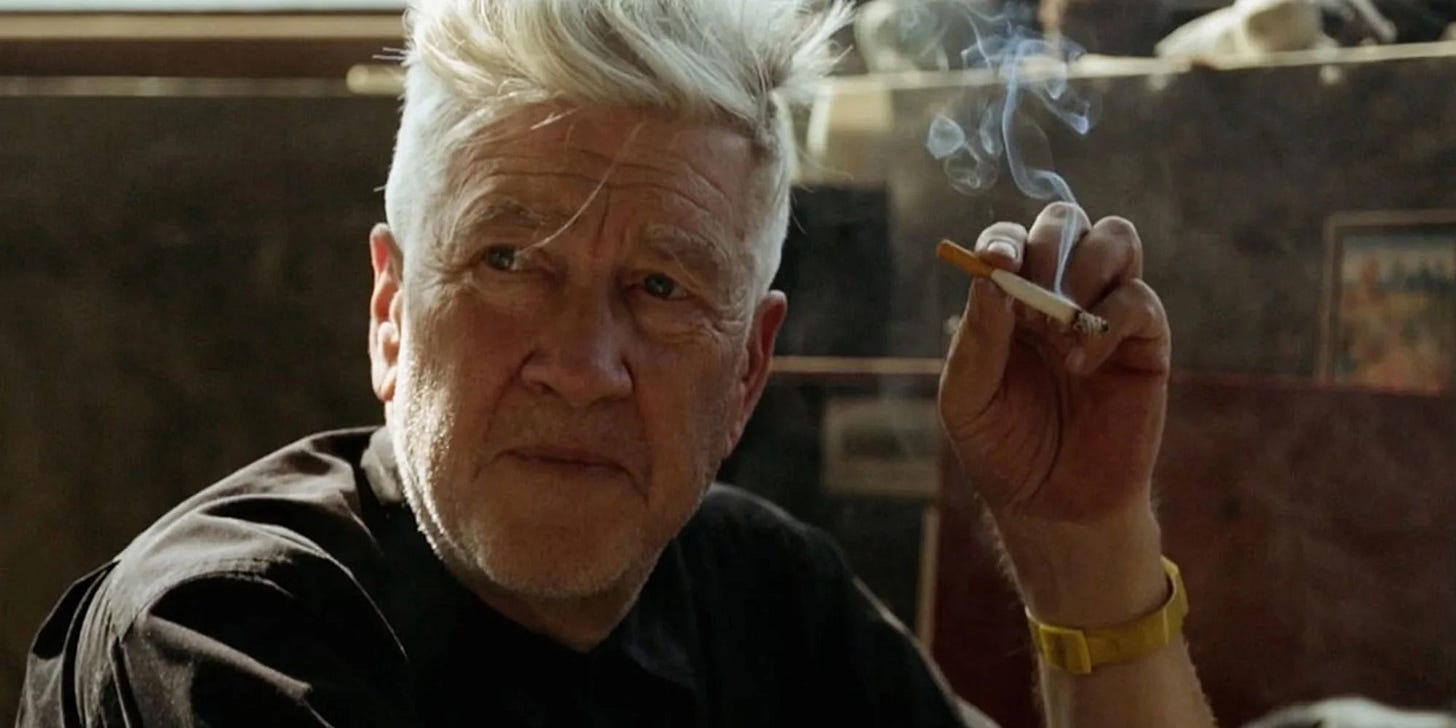

I remember the time I met David Lynch like it was meeting some distant and elusive relative. There was a weird sense of having tried for years to get in touch with this person, a man who’d become the stuff of legend. Though of course that wasn’t the actual reality, the warmth and intimacy he radiated during the meeting was of that special type one encounters with distant relatives, a kind of detectable family likeness.

Indeed, if there was one takeaway from the meeting, it was that I had spent the afternoon with one of the most human people I'd ever met, had partook of an easy kinship with essentially a stranger.

It was 2007 or 2008—a fuzzy time in my life, so, yes, “dates”—and I was still playing with my old band Interpol. The band’s manager at the time had somehow performed the spectacular networking feat of hooking up this meeting for us, knowing how often we spoke of Lynch’s work in interviews and in band meetings.

At the time, Lynch was in the course of taking one of his infamous creative forays into non-cinematic territories. He’d already established his coffee brand, but now he was “talking to bands,” so we had heard. He had been collaborating with Danger Mouse and a host of other artists, apparently, and we were all champing at the bit to try to throw our hat in the ring and get the director’s attention. When it was announced that we were to all be in LA one day so we could be driven over to the director’s mansion in Hollywood, we were ecstatic.

We sat with him in that mansion—the very same one whose front door was immortalized in Lynch’s 1997 Lost Highway—for about an hour or so, drinking coffee and shooting the breeze around his table as we talked about art. David’s experience with transcendental meditation was well-known. It was also evident at the meeting. I remember his level of attentiveness as any one of us spoke, a kind of direct attention to which I was ill-accustomed at the time. I was still an “all over the place” rock star, so it was unfamiliar to be communicating at such a high vibrational level, though David made it easy.

I remember coming away from the meeting a little depressed. At the time, my relationship with my bandmates was beginning the free fall that would eventually result in my departure. There was something about this meeting, with its luminous cast, its august tenor, its tonal richness, that felt utterly foreign to me. I realized that I was in a wholly separate process than the one implied in this meeting. There were many personal affairs that needed attending before I would ever be in a position to contribute to any future collaboration with this luminary.

If, at the time, I had already begun a certain irreversible alienation from the prospect of continuing in this type of music career, this meeting with one of the greatest directors of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries, a man whose work had been, since my early 20s—and continues to be today—a crucial touchstone for my creative process, only accelerated the growing separation. I knew that, after saying good-bye and getting back in the car and performing the customary reports to my friends that I had met my idol, I would in all likelihood never be seeing him again.

As the meeting concluded, David asked us if we wanted to leave with some of his coffee. He had a phone with an intercom at the table and was pressing the button to get his staff’s attention. When they asked him how he wanted the coffee to be served David said, “No, not served. Beans. In a bag.”

Like his German contemporary Werner Herzog, whose 2009 My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done Lynch produced—and like Hitchcock before them—David’s cadence was unmistakeable and sui generis. With its open plains accent and loud, artificial variable staccato, it was as though FBI Director Gordon Cole, his character in the beloved Twin Peaks series, had suddenly materialized in front of us as he asked for coffee and fumbled over an intercom.

Only it was the other way around, a reversal that signaled the living authenticity of this great man. For it was really David Lynch who had materialized in front of the whole world, when he came to audiences as that unforgettable character in Twin Peaks.

Like Orson Welles, Lynch became an infamous critic of the studio system in his later life. The “too many cooks” debacle of his 1984 Dune is well-known and resulted in a sworn oath that, from that point forward, he would never again make a film over which he did not have full control of final cut. If the quality of his subsequent oeuvre, a cavalcade of masterpieces, is anything to go by, it appears the promise was salutary for the history of cinema.

His final three films (not counting 1999’s amazing, though anomalous, The Straight Story), Inland Empire (2006), Mulholland Drive (2001) and Lost Highway (1997), each bear a clear stamp of the director’s critical gaze, specifically through the lens of the City of Los Angeles itself. Each one of those films reveals an LA basking in an alien and surreal toxicity, an inhuman metropolis with an unbreathable atmosphere.

Inland Empire shows us a cosmic LA, an icy landscape from some far off moon; Mulholland Drive, his reclamation of the vision of tinseltown in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, shows us an evil LA full of monsters, mafiosos and moguls; Lost Highway, the masculinized counterpart to Mulholland’s feminized dreamscape, reveals LA as a Lacanian plenum of castration and psychic mirroring.

Each of these late masterworks reveals a consciousness of the strangeness of the Los Angeles experiment, an idea that has become current as the world watches LA burn. The dystopic vision of a Los Angeles in flames, as the result of the combination of forest fires and the Santa Ana winds, has been widely commented on for a while now. Joan Didion famously dramatized those winds in her essay “The Santa Anas,” writing of a city “close to the edge.” There is a viral Joe Rogan clip from earlier last year in which he recounts an LA fireman saying it’s only a matter of time before LA burns. The idea of an LA as an instance of hubris, a desert connected to a water pipe, the plot hinge of another paean to LA in Polanski’s Chinatown, has become more familiar than ever to the rest of the country.

The latest reports show that the largest of the LA fires, the Palisades fire, is 22 percent contained, which, at least compared to several days ago, is cause for hope that LA’s incendiary nightmare is finally under control. I hope I’m not jinxing it in saying so.

It does, of course, make much of a prophet out of Mr. Lynch. It’s almost impossible not to connect the dots, to see some sort of rhyming scheme between the fires in the West Coast and the vision of a dark Americana in the director’s work.

Yet, if my own experience with the great director is anything to go by, we might say that the prophetic is itself a function of deep humanity. David’s living, breathing authenticity, so palpable at the meeting, his kindness, generosity and luminousness, must all be a factor in how we come to understand his great work, much of which is profoundly disturbing work, for posterity. It is only through the openness of the man’s soul that we are able to peer, with honesty and courage, into the darkest corners of life.

The strangeness of mourning someone whom I had only met briefly is, I suppose, a natural occurrence for someone so affected by the work of another artist. Perhaps this strangeness is merely one species of a particular overall genus of strangeness, the documentation of which David Lynch had made his life’s work.

The bowels into which he gleefully led us through his work, like a Virgil taking a Dante farther and farther down into the pit of hell, if only to reveal ever more profound layers of truth to the human experience, are now broadcast for all the world to see in the deep, dark human contradictions that assuredly play a large role in the cause of the LA fires. One can’t help but see even in this tragic and sorrowful event a glimmer of the profundity of human darkness which few other artists were so capable of revealing. May this great, authentic, powerful artist and human rest in peace.

When I read of DL's passing, I was also thinking of you, my friend. Wishing you well.

Recently I've been quite affected by Twin Peaks the return. The themes of nostalgia and not being able to return home have a dissonant resonance in my life at the moment. I will indulge and tell you that Antics (released the week I was born in 2004) has been a soundtrack for this. "When the cadaverous mob saves its doors for the dead men you cannot leave" I can't help but think of the strained relationship I have with my father and the noise of politics buzzing around my ears like mosquitos when I hear that. I can always find a peaceful moment with a cup of black coffee though.