New Deaths, New Authenticities, Part One

May the New Year Destroy the Old (that’s what it’s for!)

This is part one of a two-part post written to ring in the new year with a sense of purpose and—hopefully—some grace.

The past is always dead. I think it’s important to not only recognize that, but also to live by it.

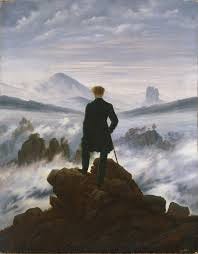

Growing up I was always looking ahead, utterly preoccupied with the future. My imago of the self is of the prophet, the man on top of the cliff looking at what lies ahead, like the appropriated Nietzsche imposed onto the Caspar David Friedrich painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, the one made famous on the cover of the posthumous edition of the philosopher’s last book Ecce Homo, back turned towards you, already moving on, looking at the skies.

This is something I’m somewhat hardwired for. It’s my default. I am afraid of the past, terrified of its frozen nature. My disgust with nostalgia bears the imprint of this fear: I have instituted an ideological regime that decries the past, all as a kind of pacifier for this fear.

But there’s little I can do about this ontological fear. Instead, I think it’s important to accept it and live according to it, without indulging it.

I often have nightmares of being chased by clandestine and deadly forces. Sometimes they are groups of people. Sometimes they are ghosts. Sometimes it is some dark, unnameable sensation, as though I were fleeing a freezing temperature filling the space with frost.

I realize now that these nightmares represent some part of me that wants to take me over, but which it is incredibly important that I stop from doing so by killing it. It is the past which threatens me and wants to treat me as though I were a husk within which it may live on forever. Nothing wants to die.

These things will stop chasing me when I decide to have the courage to destroy them.

But their destruction, the destruction of the past, poses a problem for those who wish to consider themselves authentic. Because the narrative of authenticity, the one that is most commonly understood, is somewhat predicated on the notion of consistency, that you shall continue to live on in the same way for all of your days.

There’s another side to authenticity, though. The act of self-invention, which inherently requires an abandonment of the past, a willful act of inconsistency, is also an integral part of the authentic. Without this sort of “get out of jail free card,” the ability to instantiate the utterly novel, what we know as the human experience, with its free will and its search for right action, would fall apart as a concept.

As fitting for my generation, I am an authenticity-monger. I am quite unfashionably preoccupied with consistency, sameness and spiritual depth, all markers of what is commonly understood as constituting an authentic character.

Ironic though it is—consistency, sameness and spiritual depth are not the first things that pop into my mind when I try to describe the values which are most important to me—these traits serve as benchmarks for me in my quest to sense myself as an authentic person.

And because I have chosen to live by other priorities, such as flouting the expected for the sake of it, I constantly feel inauthentic. Which in turn fuels my drive to achieve authenticity—a vicious circle.

I suspect that it is this paradox inlaid in the experience awaiting anyone who undertakes the project of authenticity which drives the current context’s manic dismissal of the authentic.

Why should you try to attain something that contradicts itself?

Doesn’t this prove that the project is, contrary to what it claims, inherently false?

Isn’t authenticity a ruse, a distraction, an imposition of some sort, designed to keep you guessing all your life instead of getting what you really want, which is to do whatever you want, authenticity be damned?

I suppose that, while these questions may satisfy a lot of people these days, I wouldn’t be having the kind of aforementioned persecution nightmares if I truly believed that things were simple enough such that some yolk of authenticity might easily be cast off by merely saying “let me do what I want.”

Rather I now believe that one indeed has a responsibility towards the past, towards the cold hand reaching for your collar from yesterday. One is to be held responsible for the spirits from the past which make authentic claims on your present.

But at the same time, this doesn’t mean that you have to believe everything the past tells you. It just means that you have to take seriously the claim that it is making. You have to turn towards it. Believing that you can simply snap your fingers and whisk yourself away into some magical realist dimension of constant self-invention won’t cut it. The nightmares will still come.

And so what happens when you take these claims from the past seriously?

Sometimes you have to negate them, as though you were Simon-what’s-his-face from American Idol telling a hopeful contestant that they’re just not good enough to get to the next level.

Sometimes you just need to make the call, you must assume an authoritarian dictatorship over what you choose to include in your present life and what you don’t.

You can’t accept every petition, every claim on your existence. In the same way that modern life is often a game of attention, where and for how long do you choose to rest your eyeballs on something, so the game of authenticity involves this internal system of review and the stamping of approval or rejection.

Like in all undemocratic exercises, one is advised to be careful with this power. You can’t be arbitrary and you can’t be capricious. That would indeed assure the return of those nightmares.

No, you still must obey a higher power than your own dictatorial will to kill the parts of the past that no longer serve you. There is still a need to obey what the truth says. This isn’t an objective truth but a spiritual one, something that comes both from the within of your psyche and from the without of the cosmic or divine.

“Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?” This line, while Saul of Tarsus was on the road to Damascus (where our word “Damascene” comes from), is perhaps the first instance in recorded history of a submission to this type of subjective truth.

Paul killed Saul at that moment. Paul killed the Saul that he was. The past was destroyed. Authenticity was won.

But this only happened as a final submission to a truth that came to him in a flash, in the form of an epiphany. Paradoxically, it was a choice that was imposed on Saul. A deal which he couldn’t refuse, as it were.

The great Harry Stanton plays Saul/Paul in The Last Temptation of Christ and there’s a scene during a fictional (and once controversial) sequence in the film, when Jesus chooses to forsake the cross and become merely mortal, where he encounters Paul preaching about the great Jesus Christ and how he forgives your sins.

Jesus, who is trying to enjoy his choice to be mortal, tells Paul he’s wrong, that he himself is Jesus of Nazareth and has chosen no such life and that Paul should stop preaching lies.

Paul turns to him and says (paraphrasing the script here) “I don’t care who you are. I have already been saved by the power of Christ. And I will go on preaching of his love, for me, and for you.”

What this is is a story of the way that myth can sometimes be truer than fact. The meaning of Christ, the choice towards authenticity which Paul had accomplished on his way to Damascus, was exponentially truer than the actual physical embodiment of the human being of Jesus of Nazareth being presented to him in the flesh.

Authenticity is, in this sense, itself an act of self-invention, a creation of a new reality, accomplished in collaboration with the divine, involving the destruction of the past.

As an artist, I am no stranger to the way that expectation follows you like a shark.

Life is long and sometimes you decide that what worked for you before is never going to work for you again.

But this decision, being somewhat a private affair, seems to have little impact on the expectations that hound you, those expectations being fomented by the rather public art you made in the past, an art which you have decided to leave behind.

It’s important in these cases to be humble towards the past. One must understand the forces at work and have compassion for the way that art lives on in the hearts of the many who were touched by it.

But this doesn’t mean that it should live on in one’s own heart if one has already decided to kill that part of oneself and go on to other pastures.

My previous art lives on within me in the form of pride, in the way that an old photo showing someone holding a trophy should inspire pride for them.

But it would be a mistake to infer that whatever sport one mastered in order to garner that trophy should be pursued in perpetuity. The human body, with its aging process, can tolerate no such thing. The recent matchup between Mike Tyson and Jake Paul is just one garish example among many of the absurdity of this type of nostalgia.

In many respects I am still searching for my new role, for my new authenticity, my new act of self-invention. Many times it feels like things haven’t clicked for me, at least not in the way that it seemed like they had clicked for me in the past.

At fifty, it can be painful to continue on in this quest.

But I don’t really have a choice in whether or not I now know what my next authenticity is. I have to wait and press on until my new Damascene moment comes to me.

I was very lucky in my twenties. I met the right people at the right time in the right place with the right intentions searching for the right opportunities. This unimaginable luck thrusted me to a place of magic and grace and power. To this day, I enjoy the fruits of having stumbled onto such wild luck while I was studying Philosophy at NYU in 1997.

What is also true is that one of the most important of the things that made me famous, the instrument for which I am widely credited and celebrated, is not an instrument that I particularly care all that much about, nor really ever did. At least not in any extraordinarily special way. I always did and continue today to care much more about other instruments and other practices than the one for which the cosmos had chosen me at that time.

My decision to play that instrument was a rather mercenary one. I knew how to play the guitar, but that was not the space that was available. I decided to parlay my ability to play the guitar to become a good enough bass player such that the band I wanted to be a part of could go on playing live. But that was basically it. Since leaving that band fifteen years ago, I can almost count on two hands the number of hours I’ve spent playing that instrument.

I have killed that part of me, that part of me who was willing to be good at something that didn’t speak to him all the way down to his soul, but which was good enough, more than good enough, for the time. That part of me no longer exists. He is in the past.

Today, and forever after from this early point in the year 2025, I wish to live only for the things that speak to me at the most profound level, no matter how many eyeballs that attracts, no matter how many disappointments it causes, no matter how many successes it engenders. Those things shall come second to the first thing, to the new authenticity.

I wish the same for you. That you may in this new year find your new authenticity, that you destroy what needs to be destroyed, that you may be given the opportunity to experience the confluence of your will with that of the cosmos.

Happy New Year!

An inspiring and enjoyable article Carlos, thank you - HNY! (Numerology aficionados will have noted that 2025 is a rare - and hopefully propitious - perfect square year, with the next one not due until 2116). I try to be authentic too, but if I can't, then I am at least authentically inauthentic.

"And then the past recedes, and I won't be involved. The effort to be free, seems pointless from above." - John Frusciante

Happy New year Carlos Dengler. I've appreciated your ambient music throughout 2024, and more recently found a gem with your essays.