The Frozen Kiss

How pop culture materials and sentimentality intertwine and what we might want to consider doing about it

Please read the latest edition of The Red Hand Files, Nick Cave’s often touching, often frustrating, soul-baring, real time conversation with his fans in newsletter form, an unfolding, ongoing encomium to the world, both inner and outer, of the creative process.

In this one he lays out what I consider to be a precise account of the power of the live performance. As a former live performer I can say that I identified greatly with Cave’s observations of the concert as “powerfully and empathetically transactional“ and also of “the therapeutic nature of the music.”

But, as some of you probably already know, I am a great skeptic of the ability of contemporary culture and the entertainment industry to permit, with any meaningful degree of regularity, the kind of engagement that Cave speaks about. To be fair to him, he is an example of the rare commodity in late capitalism, a sui generis pop artist playing by his own rules, delivering meaningful creative engagement between him and his audience well into his silver years. All artists should be so lucky to be able to enjoy for so long this kind of uninterrupted connection between the primal artistic act of performance and the honest, present reception of it by the audience.

This rare freedom, I believe, is largely a matter of genre: in essence, Cave is a singer-songwriter, the lone world builder atop his creative universe. The intimacy that he enjoys between himself and his audience is to a large extent baked into the conventions and expectations of the genre, something it shares with, for example, folk music.

Figure and background are in a severe dynamic in this form of art, where instrumentation and orchestration serve as the “landscape” to the heroic arc of the single voice in close-up. This is one of the reasons why I consider someone like Leonard Cohen to have been successful in viably offering audience engagement right up to his last years (he died at 82 and was performing almost up to the end): singer-songwriters age well, along with their audiences. The flexibility of their art form enables this dynamic across decades.

But I want to home in a little bit on a curious aspect of Cave’s most recent post in The Red Hand Files.

Because I think what’s usually charming about this newsletter, its intimate voice and assertive defense of the primacy of the creative process, is what here might be its blindspot, preventing Cave from the acknowledgement of the inherent nostalgia baked into the commodity form of the live performance in pop music.

To be sure, Nick Cave is absolutely correct in questioning the letter-writer’s early departure from his concert. He is 100% right that his live performance, especially one in his genre, had the capacity to potentially heal the wound that was being opened up by the letter-writer’s remembrance of the painful memory triggered by the song. And, in this sense, one might say that it was unfortunate that the letter-writer could not “stick it through.”

Of course, no one but the letter-writer himself knows the level of heartbreak he was experiencing in the moment. We should absolutely stay our impulses to recommend courses of action based off of what we all believe someone should be doing with their pain. Such matters are always up to them.

At any rate, what I think Cave misses (and this is not to say that I know if Cave even cares about critical theory or anything of the sort, nor that one should expect him to care about it - maybe he does but that is beside the point) is the role of nostalgia that is being brought to a glaring light by the letter-writer’s admission.

Because, to me, it is a fact that part of the letter-writer’s reaction to the performance of a song that “brought him back” to a precious and painful moment in his life, a perfectly legitimate feeling tied to a perfectly legitimate experience, is actually also a site of commercial instigation for the entertainment industry. The imbrication of pop culture materials such as songs within the experiential nexus of modern life, one’s lived experience, is precisely a strategy, which has accrued over decades of market streamlining and corporate mergers, that manufactures reliable consumer engagement with ever increasing precision.

It is truly difficult in the modern world’s vast complex of entertainment options to parse out one’s legitimate emotional reactions to beloved artistic works and the ways in which these legitimate reactions are being amplified and exploited to funnel profits. I am not here to criticize anyone who does not feel it particularly important to have to perform these kinds of separations. Like what you like—and pay what you will for liking what you like. In the realm of culture, especially compared to more important global concerns, one can’t say any real harm is being done.

So, setting aside any concerns over accountability, the topic nonetheless deserves attention. Because culture says a lot about us and if culture at the moment seems to be wedded to industry in such a way as to nullify its authentic reflection of our hopes and dreams, then I think it is worth spending time on the question about nostalgia which—I think it’s pretty clear by this point—performs a massive role in what attracts us to certain cultural products.

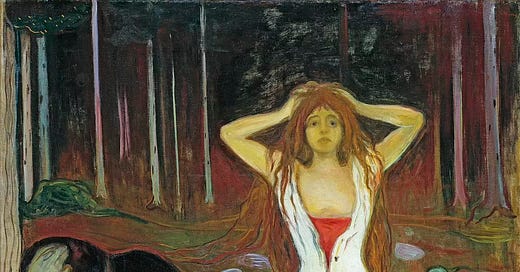

In my view, the letter-writer was responding to an ongoing relationship between pop culture and memory. Memories charged with romance and emotion, the kind we encounter in heightened form when we are young, are utterly intertwined with the pop culture form, especially in its musical variety. This is why if you meet someone at a concert that you end up marrying, chances are you will always go back as a couple to see that artist perform live over the years to perform a kind of “reunion” or “anniversary” celebration of your relationship. The two events, the live performance, an instance of culture, and the meeting, a personal event, are from that point forward brought together and sealed, like a frozen kiss.

In this way it is apparent the extent to which the entertainment industry relies on audience sentiment, as opposed to audience discernment, in order to activate the transaction of a concert performance, a transaction upon which a great deal of its profits are dependent.

The reason why I find it important to focus on this aspect of the consumption process of pop culture, besides the obvious fact of the experience I have having been on one side of the divide between performer and audience, is that I consider it conspicuously messy when I read stories like that of the letter-writer’s.

I have no words to say about whether or not he should have stayed at the concert. Again, only he is in a position to make that call.

Nor do I feel that Nick Cave should have responded to him in any other way than his prescription for surrender to the Dionysian interchange of the ensuing concert performance.

It’s only that I find it telling that the letter-writer had such a strong reaction in the first place. And rather than simply assume that these kinds of emotional reactions to pop culture materials are indeed integral to the art form, I think it’s better to interrogate that assumption and ask whether or not the role nostalgia plays in our consumption of pop cultural materials has not reached the level of a runaway train.